January 2022

Subscribe to Dialogue

FEATURED BOOKS AND DVDS

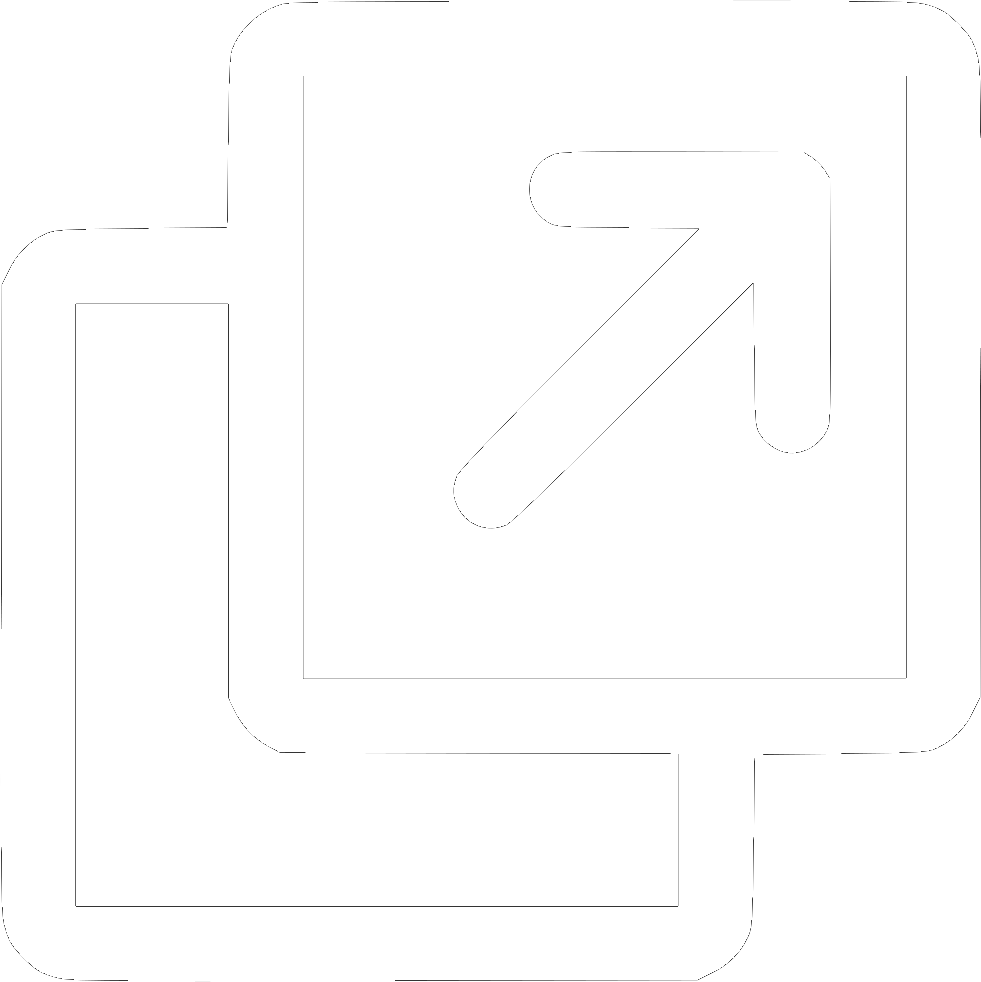

Paperback / $22.00 / 138 Pages / full colour

For more than two millennia, informed observers of nature believed that it was possible for an organism to pass on acquired characteristics to offspring. This was specifically the notion that an organism has the capacity to pass to its offspring physical characteristics acquired through use or disuse of an organ. Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829) promoted the ancient Greek idea of inheritance of acquired characteristics with the implication that these results would be cumulative through subsequent generations. Darwin himself promoted a similar notion with his concept of pangenesis.

Both Lamarckian inheritance and pangenesis were later discredited by neo-Darwinian theory. However Russian Trofim Denisovich Lysenko (1898-1976) became a 20th century promoter of environmentally acquired inheritance. He became Director of the Institute of Genetics in 1940 and Russian agriculture was soon thoroughly based on his ideas. Critics were harshly dealt with. There were multiple years of crop failures in Russia and China as a result of Lysenko’s ideas. This man’s influence however waned in Russia after Stalin’s death (1953) and eventually also in China. It seemed as if Lamarck’s ideas were finally dead.

But old ideas have a habit of coming back into prominence, often under a new name. In the case of Lamarckian theory, it has returned as the popular theory of epigenetics. The term ‘epigenetics’ had been around since the 1940s, but its significance was formally recognized in 2008 when it was defined as changes to the physical and/or behavioural expression of an organism as a result of markers added to the germline in his/her parents which affect not the actual sequence of nucleotides, but controls on how those nucleotides are read. These changes can be passed on to several generations, but are reversible and will eventually disappear. The reason for the appearance of new markers seems to be environmental or behavioural impacts. Thus, we see that epigenetics is a more technical term for the inheritance of acquired characteristics.

Possible epigenetic changes include DNA methylation. When a methyl group (-CH3) is attached to specific sites along the DNA molecule it will block proteins that need to attach to the DNA at that spot in order to initiate transcription of a certain gene. Thus, methylation turns genes off, while demethylation (loss of the methyl group) turns genes on. Chemical groups can also be added or removed from histones, thus changing access to the gene, whether it is unwrapped (on) or wrapped (off).

One of the most famous recent examples of epigenetics/inheritance of acquired characteristics is the “Hunger Winter” in the Netherlands during the waning days of the second world war. This was a time of extreme scarcity of food for the Dutch people in the east of the country, especially in the cities. It has since been discovered that babies which were in utero (unborn) at this time, are much more prone to diseases like diabetes II as a result of epigenetic marks acquired by their chromosomes when their mothers were near starvation. Some of these impacts have been passed on to the next generation as well. This is a classic case of the impact of environmental conditions on subsequent generations.

The significance of this process is to demonstrate yet another layer to the complex genetic controls of living cells. Moreover, something that is temporary in effect (several generations at most), and often promotes disease, is not going to be helpful for advancement through evolutionary processes. Probably at most what we can say is that epigenetics helps populations adjust to temporary current conditions, but it does not hold promise for any long term trends and certainly not evolution.

Order OnlinePaperback / $6.00 / 55 Pages

For more than two millennia, informed observers of nature believed that it was possible for an organism to pass on acquired characteristics to offspring. This was specifically the notion that an organism has the capacity to pass to its offspring physical characteristics acquired through use or disuse of an organ. Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829) promoted the ancient Greek idea of inheritance of acquired characteristics with the implication that these results would be cumulative through subsequent generations. Darwin himself promoted a similar notion with his concept of pangenesis.

Both Lamarckian inheritance and pangenesis were later discredited by neo-Darwinian theory. However Russian Trofim Denisovich Lysenko (1898-1976) became a 20th century promoter of environmentally acquired inheritance. He became Director of the Institute of Genetics in 1940 and Russian agriculture was soon thoroughly based on his ideas. Critics were harshly dealt with. There were multiple years of crop failures in Russia and China as a result of Lysenko’s ideas. This man’s influence however waned in Russia after Stalin’s death (1953) and eventually also in China. It seemed as if Lamarck’s ideas were finally dead.

But old ideas have a habit of coming back into prominence, often under a new name. In the case of Lamarckian theory, it has returned as the popular theory of epigenetics. The term ‘epigenetics’ had been around since the 1940s, but its significance was formally recognized in 2008 when it was defined as changes to the physical and/or behavioural expression of an organism as a result of markers added to the germline in his/her parents which affect not the actual sequence of nucleotides, but controls on how those nucleotides are read. These changes can be passed on to several generations, but are reversible and will eventually disappear. The reason for the appearance of new markers seems to be environmental or behavioural impacts. Thus, we see that epigenetics is a more technical term for the inheritance of acquired characteristics.

Possible epigenetic changes include DNA methylation. When a methyl group (-CH3) is attached to specific sites along the DNA molecule it will block proteins that need to attach to the DNA at that spot in order to initiate transcription of a certain gene. Thus, methylation turns genes off, while demethylation (loss of the methyl group) turns genes on. Chemical groups can also be added or removed from histones, thus changing access to the gene, whether it is unwrapped (on) or wrapped (off).

One of the most famous recent examples of epigenetics/inheritance of acquired characteristics is the “Hunger Winter” in the Netherlands during the waning days of the second world war. This was a time of extreme scarcity of food for the Dutch people in the east of the country, especially in the cities. It has since been discovered that babies which were in utero (unborn) at this time, are much more prone to diseases like diabetes II as a result of epigenetic marks acquired by their chromosomes when their mothers were near starvation. Some of these impacts have been passed on to the next generation as well. This is a classic case of the impact of environmental conditions on subsequent generations.

The significance of this process is to demonstrate yet another layer to the complex genetic controls of living cells. Moreover, something that is temporary in effect (several generations at most), and often promotes disease, is not going to be helpful for advancement through evolutionary processes. Probably at most what we can say is that epigenetics helps populations adjust to temporary current conditions, but it does not hold promise for any long term trends and certainly not evolution.

Order OnlineHardcover / $52.00 / 433 Pages

For more than two millennia, informed observers of nature believed that it was possible for an organism to pass on acquired characteristics to offspring. This was specifically the notion that an organism has the capacity to pass to its offspring physical characteristics acquired through use or disuse of an organ. Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829) promoted the ancient Greek idea of inheritance of acquired characteristics with the implication that these results would be cumulative through subsequent generations. Darwin himself promoted a similar notion with his concept of pangenesis.

Both Lamarckian inheritance and pangenesis were later discredited by neo-Darwinian theory. However Russian Trofim Denisovich Lysenko (1898-1976) became a 20th century promoter of environmentally acquired inheritance. He became Director of the Institute of Genetics in 1940 and Russian agriculture was soon thoroughly based on his ideas. Critics were harshly dealt with. There were multiple years of crop failures in Russia and China as a result of Lysenko’s ideas. This man’s influence however waned in Russia after Stalin’s death (1953) and eventually also in China. It seemed as if Lamarck’s ideas were finally dead.

But old ideas have a habit of coming back into prominence, often under a new name. In the case of Lamarckian theory, it has returned as the popular theory of epigenetics. The term ‘epigenetics’ had been around since the 1940s, but its significance was formally recognized in 2008 when it was defined as changes to the physical and/or behavioural expression of an organism as a result of markers added to the germline in his/her parents which affect not the actual sequence of nucleotides, but controls on how those nucleotides are read. These changes can be passed on to several generations, but are reversible and will eventually disappear. The reason for the appearance of new markers seems to be environmental or behavioural impacts. Thus, we see that epigenetics is a more technical term for the inheritance of acquired characteristics.

Possible epigenetic changes include DNA methylation. When a methyl group (-CH3) is attached to specific sites along the DNA molecule it will block proteins that need to attach to the DNA at that spot in order to initiate transcription of a certain gene. Thus, methylation turns genes off, while demethylation (loss of the methyl group) turns genes on. Chemical groups can also be added or removed from histones, thus changing access to the gene, whether it is unwrapped (on) or wrapped (off).

One of the most famous recent examples of epigenetics/inheritance of acquired characteristics is the “Hunger Winter” in the Netherlands during the waning days of the second world war. This was a time of extreme scarcity of food for the Dutch people in the east of the country, especially in the cities. It has since been discovered that babies which were in utero (unborn) at this time, are much more prone to diseases like diabetes II as a result of epigenetic marks acquired by their chromosomes when their mothers were near starvation. Some of these impacts have been passed on to the next generation as well. This is a classic case of the impact of environmental conditions on subsequent generations.

The significance of this process is to demonstrate yet another layer to the complex genetic controls of living cells. Moreover, something that is temporary in effect (several generations at most), and often promotes disease, is not going to be helpful for advancement through evolutionary processes. Probably at most what we can say is that epigenetics helps populations adjust to temporary current conditions, but it does not hold promise for any long term trends and certainly not evolution.

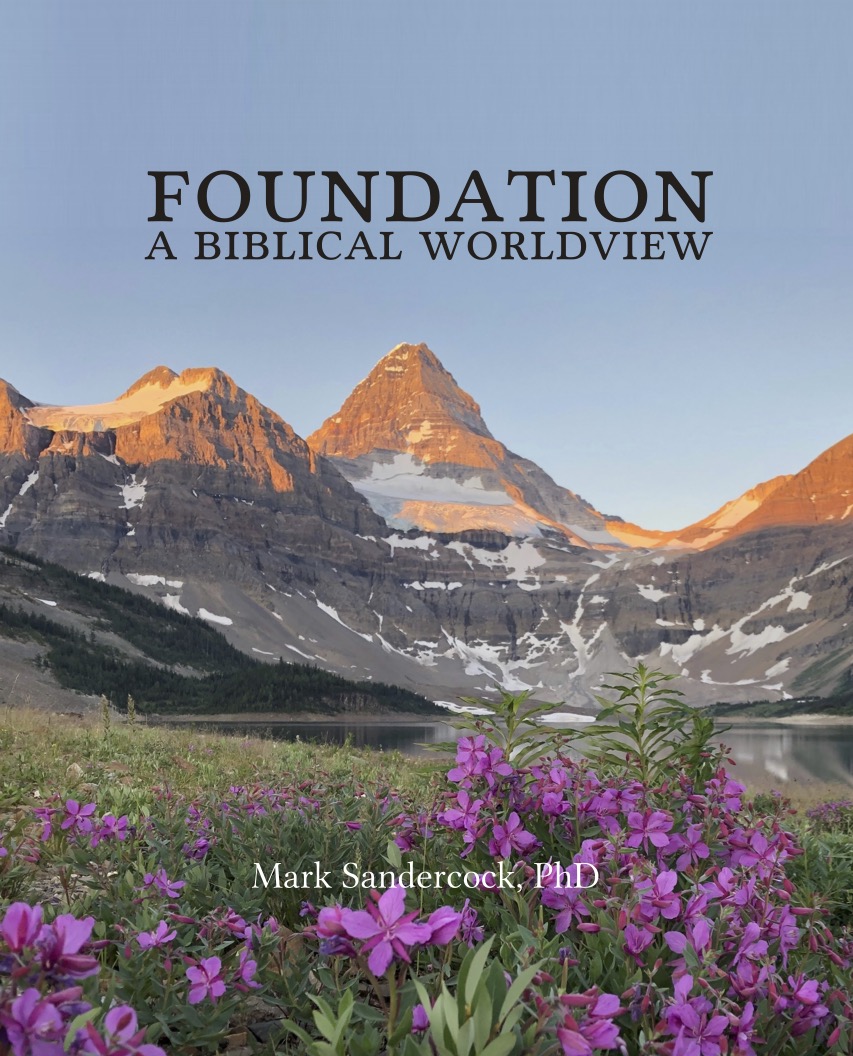

Order OnlinePaperback / $28.00 / 256 Pages

For more than two millennia, informed observers of nature believed that it was possible for an organism to pass on acquired characteristics to offspring. This was specifically the notion that an organism has the capacity to pass to its offspring physical characteristics acquired through use or disuse of an organ. Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829) promoted the ancient Greek idea of inheritance of acquired characteristics with the implication that these results would be cumulative through subsequent generations. Darwin himself promoted a similar notion with his concept of pangenesis.

Both Lamarckian inheritance and pangenesis were later discredited by neo-Darwinian theory. However Russian Trofim Denisovich Lysenko (1898-1976) became a 20th century promoter of environmentally acquired inheritance. He became Director of the Institute of Genetics in 1940 and Russian agriculture was soon thoroughly based on his ideas. Critics were harshly dealt with. There were multiple years of crop failures in Russia and China as a result of Lysenko’s ideas. This man’s influence however waned in Russia after Stalin’s death (1953) and eventually also in China. It seemed as if Lamarck’s ideas were finally dead.

But old ideas have a habit of coming back into prominence, often under a new name. In the case of Lamarckian theory, it has returned as the popular theory of epigenetics. The term ‘epigenetics’ had been around since the 1940s, but its significance was formally recognized in 2008 when it was defined as changes to the physical and/or behavioural expression of an organism as a result of markers added to the germline in his/her parents which affect not the actual sequence of nucleotides, but controls on how those nucleotides are read. These changes can be passed on to several generations, but are reversible and will eventually disappear. The reason for the appearance of new markers seems to be environmental or behavioural impacts. Thus, we see that epigenetics is a more technical term for the inheritance of acquired characteristics.

Possible epigenetic changes include DNA methylation. When a methyl group (-CH3) is attached to specific sites along the DNA molecule it will block proteins that need to attach to the DNA at that spot in order to initiate transcription of a certain gene. Thus, methylation turns genes off, while demethylation (loss of the methyl group) turns genes on. Chemical groups can also be added or removed from histones, thus changing access to the gene, whether it is unwrapped (on) or wrapped (off).

One of the most famous recent examples of epigenetics/inheritance of acquired characteristics is the “Hunger Winter” in the Netherlands during the waning days of the second world war. This was a time of extreme scarcity of food for the Dutch people in the east of the country, especially in the cities. It has since been discovered that babies which were in utero (unborn) at this time, are much more prone to diseases like diabetes II as a result of epigenetic marks acquired by their chromosomes when their mothers were near starvation. Some of these impacts have been passed on to the next generation as well. This is a classic case of the impact of environmental conditions on subsequent generations.

The significance of this process is to demonstrate yet another layer to the complex genetic controls of living cells. Moreover, something that is temporary in effect (several generations at most), and often promotes disease, is not going to be helpful for advancement through evolutionary processes. Probably at most what we can say is that epigenetics helps populations adjust to temporary current conditions, but it does not hold promise for any long term trends and certainly not evolution.

Order OnlinePaperback / $16.00 / 189 Pages / line drawings

For more than two millennia, informed observers of nature believed that it was possible for an organism to pass on acquired characteristics to offspring. This was specifically the notion that an organism has the capacity to pass to its offspring physical characteristics acquired through use or disuse of an organ. Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829) promoted the ancient Greek idea of inheritance of acquired characteristics with the implication that these results would be cumulative through subsequent generations. Darwin himself promoted a similar notion with his concept of pangenesis.

Both Lamarckian inheritance and pangenesis were later discredited by neo-Darwinian theory. However Russian Trofim Denisovich Lysenko (1898-1976) became a 20th century promoter of environmentally acquired inheritance. He became Director of the Institute of Genetics in 1940 and Russian agriculture was soon thoroughly based on his ideas. Critics were harshly dealt with. There were multiple years of crop failures in Russia and China as a result of Lysenko’s ideas. This man’s influence however waned in Russia after Stalin’s death (1953) and eventually also in China. It seemed as if Lamarck’s ideas were finally dead.

But old ideas have a habit of coming back into prominence, often under a new name. In the case of Lamarckian theory, it has returned as the popular theory of epigenetics. The term ‘epigenetics’ had been around since the 1940s, but its significance was formally recognized in 2008 when it was defined as changes to the physical and/or behavioural expression of an organism as a result of markers added to the germline in his/her parents which affect not the actual sequence of nucleotides, but controls on how those nucleotides are read. These changes can be passed on to several generations, but are reversible and will eventually disappear. The reason for the appearance of new markers seems to be environmental or behavioural impacts. Thus, we see that epigenetics is a more technical term for the inheritance of acquired characteristics.

Possible epigenetic changes include DNA methylation. When a methyl group (-CH3) is attached to specific sites along the DNA molecule it will block proteins that need to attach to the DNA at that spot in order to initiate transcription of a certain gene. Thus, methylation turns genes off, while demethylation (loss of the methyl group) turns genes on. Chemical groups can also be added or removed from histones, thus changing access to the gene, whether it is unwrapped (on) or wrapped (off).

One of the most famous recent examples of epigenetics/inheritance of acquired characteristics is the “Hunger Winter” in the Netherlands during the waning days of the second world war. This was a time of extreme scarcity of food for the Dutch people in the east of the country, especially in the cities. It has since been discovered that babies which were in utero (unborn) at this time, are much more prone to diseases like diabetes II as a result of epigenetic marks acquired by their chromosomes when their mothers were near starvation. Some of these impacts have been passed on to the next generation as well. This is a classic case of the impact of environmental conditions on subsequent generations.

The significance of this process is to demonstrate yet another layer to the complex genetic controls of living cells. Moreover, something that is temporary in effect (several generations at most), and often promotes disease, is not going to be helpful for advancement through evolutionary processes. Probably at most what we can say is that epigenetics helps populations adjust to temporary current conditions, but it does not hold promise for any long term trends and certainly not evolution.

Order Online