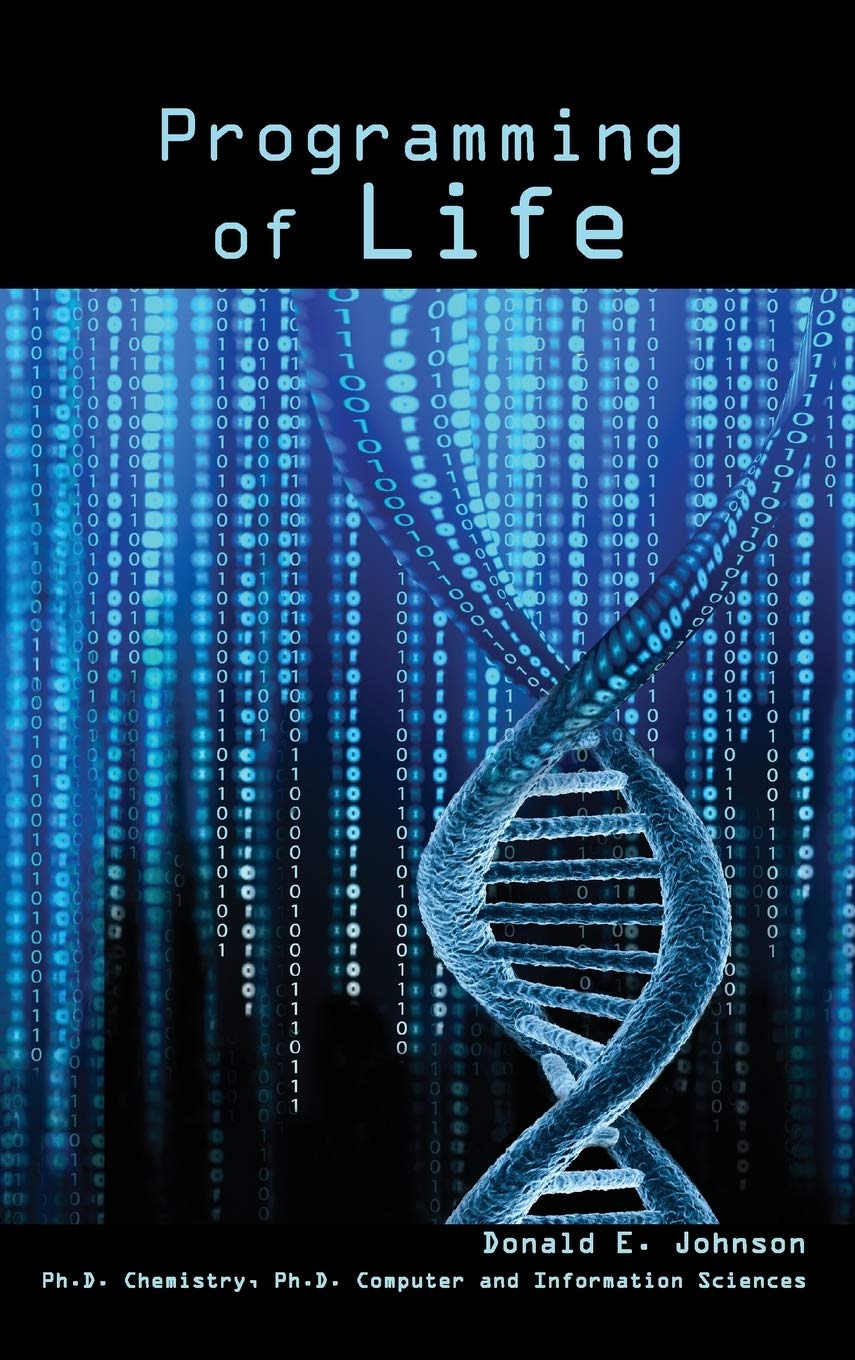

We hear all the time about how complicated living cells are. It makes us think that such entities were designed to work as they do. People who support the idea that all things came about by natural processes, however, do not want to think that there is a mind behind what we see in all living creatures from microbes up to the largest, most complicated organisms. These latter people want to show how the living cell developed spontaneously, without any direction. So they want to demonstrate that there were early cells which were much much simpler than what we see today, cells that could have appeared through natural processes. These scientists want to demonstrate that the barriers to spontaneous development are not too high.

In this context, generations of scientists have devoted themselves to origin of life studies. Thus interest was high in a major study published in March 2016. The results however were not at all what the evolutionists were looking for. When intelligent design apologist biophysicist Cornelius Hunter commented on his blog “Darwin’s God: How religion drives science and why it matters” on the significance of the new study, 125 comments were posted to his blog, most of them extremely angry and many with highly inappropriate language. What Dr. Hunter said was that these studies are making things worse and worse for evolutionists. “Simply put, “he said, “the science contradicts the theory. What the science is telling us is that evolution is impossible, by any reasonable definition of that term.”

Dr. Hunter was commenting on origin of life studies. In keeping with their interest in evolution and their belief that life originated from non-life (chemicals), many scientists have sought simpler cells than we see today. They are looking for hints about those early stages of life (if any). One scientist involved for almost two decades in pursuit of the dream of producing a simple cell, is J. Craig Venter. Dr. Venter began with a disease causing bacterium called Mycoplasma genitalium. He was able to eliminate some genes and still have a cell that could live (just barely). That was 1995. But this organism grew too slowly and was hard to work with.

Next Dr. Venter’s team switched to a similar but more robust species Mycoplasma mycoides. He started with a complete record of the nucleotide bases (like alphabet letters) in the bacterium’s DNA (genome). The 901 genes in the genome were composed of a total of one million nucleotides. As a first step in his quest to find a minimalist cell, he first set out to string together all these genes artificially and then insert them into a cell from which its own DNA had been removed. This he was able to do. The new artificial DNA was inserted into a different species of Mycoplasma from which its own DNA had been removed. And the new artificially put together genome expressed the characteristics of the former species from which its information had been copied.

This new living organism was labelled JCVI-Syn. 1.0. The significance was that an artificially pieced together string of DNA had been shown to work in directing the life activities of a cell. Of course the biologists had not developed anything original, they had simply copied an existing design (long string of nucleotides conveying information). This however was to provide the platform for further studies into a minimalist cell.

The biologists drew up a list of what genes they believed would be essential in a minimalist cell. They pieced the genes together (as they had previously with Syn.1.0) and they inserted their designed genome into a cell from which the real genome had been removed. However in this case their designed genome failed to support life. They did not really know what genes were essential to life. The bottom up approach (composing a genome based on their ideas) had failed.

So they went back to their Syn. 1.0 organism with its 901 genes. They tried knocking out various genes in order to discover how small a genome they could produce which yet supports life. Eventually they managed to knock out 428 genes. That is a lot of information eliminated!! The result was a genome of 473 genes consisting of 531,000 nucleotides. This was a major achievement. They labelled it JCVI-Syn. 3.0. The science media were very impressed and well they might be. This achievement represented a lot of careful work. However the researchers had not created any new genes of biological functions and they had merely eliminated a number of genes that were not essential for keeping the cell alive.

From the point of view of seeking a very simple primitive cell, it is obvious however that Syn. 3.0 is a failure! The cell has 473 genes and is thus still very complicated, way beyond the capacity of natural processes to develop such a system through trial and error (chance processes). And another fascinating detail is that 31% or 149 genes in this “minimalist” cell exhibit no functions that we know about. Yet the cell dies if any of them is missing! What we have learned from these studies is that there is no simple cell. Living cells require hundreds of genes (each coded for by an average of about 1000 nucleotides in a very specific order).

Scientists at the J. Craig Venter Institute in La Jolla, California had managed to reduce the number of genes in a bacterial cell down to 473 genes. If the number of genes were any fewer, the cell did not survive. Dr. Hunter, for his part, declared that this is an enormous level of complexity, far beyond evolution’s meager capacity to work with random change. (Natural selection, by the way, works only on living reproducing cells, not on systems which might be progressing toward a living condition. Thus claims that natural selection eliminates arguments concerning chance, are not valid). Most of the news stories describing this work, concentrated on what the scientists had achieved, while at the same time ignoring the scientists’ main objective which they had failed to achieve.

The living cell is obviously an all or nothing system. Either it has all the information/programming it needs (in the DNA), or it does not. The “minimalist” cell that the Venter lab produced was managed by 473 genes. Each gene in itself contains complex information too. Nobody thinks that the very same genes will be found to be the ones essential for every species. However this study provides a clear indication of the amount of information required for the living condition. Investigators previously had been able to reduce parasitic Mycoplasma genitalium down to about 375 genes, but this is a bacterium that is strongly dependent on its host for support and which does not do well outside the body of a living victim. Thus M. genitalium is not a good indication of how an original “simple” cell could manage in the environment. Yet it too is highly complex.

So Dr. Venter’s work, although interesting, has certainly been most discouraging for scientists looking for an original evolutionarily-primitive living cell. The living cell is clearly a designed system, irreducibly complex and something that could never develop on its own. Highly trained scientists have been looking for almost a century for a minimalist, primitive cell. On the contrary however what their studies are revealing, are cells which are frankly complex and full of information, obviously created!!

Margaret Helder

June 2016

Subscribe to Dialogue